Back to Project Teams?

In my previous post I have outlined how Agile methods solved some of the biggest issues organizations had with using project teams for development software. In short, we built stable, cross-functional teams that could own functionality end-to-end. Instead of building software in one large piece, we started slicing it into small, value-added chunks (e.g. User Stories). Instead of working in isolation, we focused on ongoing communication and shorter feedback loops (e.g. through Daily Standup meetings). Instead of integrating everything at the very end, we learned technical skills (e.g. continuous integration and automated testing) that enabled us to integrate and deploy software continuously. And instead of separating development from maintenance, which often led to poor quality, we created a strong feedback loop, expressed in the slogan “You build it, you run it!”

Issues With Stable Teams

Unfortunately that’s not the end of the story, because we can now observe a trend to change this paradigm again, away from stable teams. Of course stable, cross-functional teams are not perfect and have their shortcomings, and more and more organizations become aware of them:

1) The teams have a tendency to grow quite big, if we want them to be truly cross-functional. Just think about “new” skills like cloud computing or the need for higher levels of security and scalability, which make it hard to contain all the needed knowledge in a small team. Larger team size often means less efficiency and longer lead times, which nobody likes.

2) The alternative to ever growing teams is to split them up into smaller ones, which opens another can of worms. Now we suddenly have to find ways to coordinate these different teams, because they are all dependent on each other. And it turns out that this coordination of multiple teams is not trivial and often leads to poor results and a lot of frustration. (You can find all my posts about Team of Teams here).

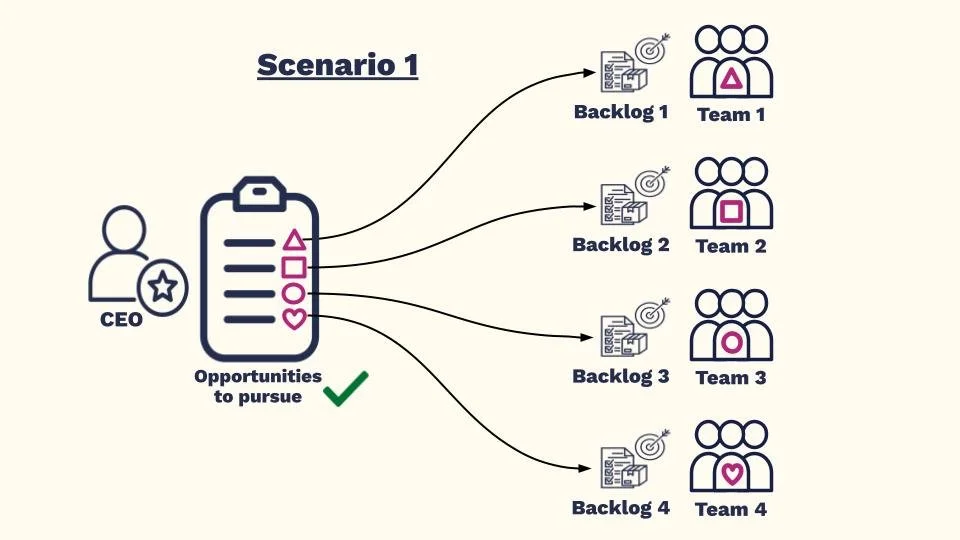

3) Every team owns a respective domain / piece of functionality, and the work for that domain is represented in a product backlog. If we zoom out to a higher level of the organization, we can see that we now have a bunch of different team backlogs, which each makes sense in itself. But from an overall business perspective, these backlogs might not represent the work with the highest priority. Let’s imagine a small company with only four development teams: Team Triangle, Team Square, Team Circle and Team Heart. The CEO regularly creates a list with the biggest business opportunities he wants to pursue. She doesn’t care about which team does the work or how it’s implemented, as long as it gets done in priority order. Best case scenario is that the first four opportunities on the CEO’s list are one Triangle, one Square, one Circle and one Heart. This way, each of the teams can work on one of the highest priority items.

Illustration 1: The existing team structure supports business priorities well.

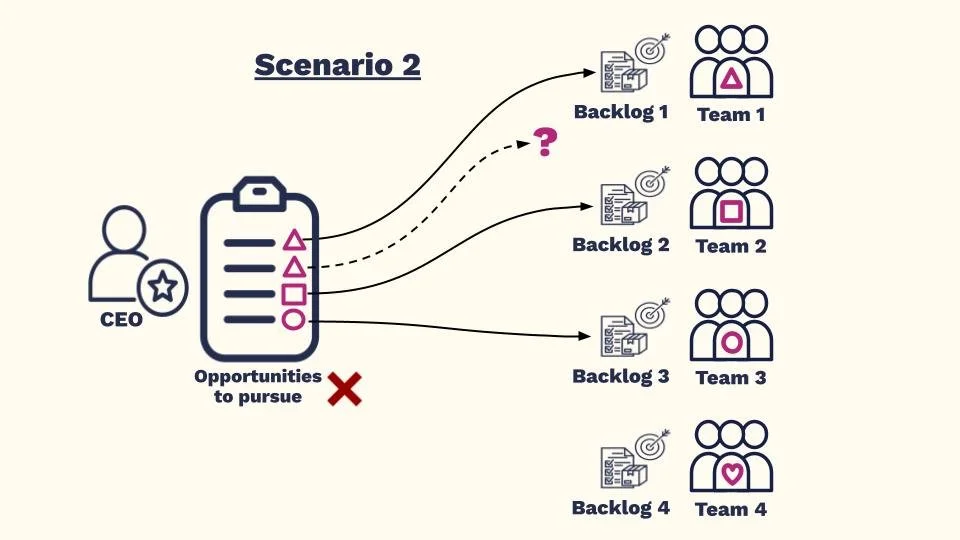

But what if the list looks differently? What if the CEO sees the biggest two opportunities in the Triangle area, followed by Square and Circle (and nothing high priority for Heart)? Now the existing team structure prevents the organization from building the most important stuff first, because team Triangle has the most two important items, while there’s nothing for team Heart.

Illustration 2: The existing team structure gets in the way of business priorities.

If we find ourselves in such a situation repeatedly, we might wonder: Wouldn’t it be better to have less rigid team structures to get more flexibility? Wouldn’t it make sense to assemble teams according to our priorities? (In our blog post Adjusting Goals to Teams? we describe how this might look like.)

The Pendulum Swings Back

My observation is that organizations often overcorrect a perceived problem and oscillate between two extremes (see this post).

We can also see this pattern in the context of team structures: The old project teams became problematic, so we moved away and formed stable, cross-functional teams instead, which provided a lot of upsides. But now the downsides of this team structure becomes more and more salient and we start looking at the other extreme again: no team stability at all. Although we use fancy terms like “fluid teams”, “teaming ” or “dynamic reteaming”, there’s a risk that we reintroduce the old project structures, which we had good reasons to get rid of. Yes, hyper-stable teams are not perfect and have some serious downsides. And yes, super-fluid project teams do have some upsides and might look tempting when we are wrestling with the issues I have outlined above. But if we simply move back to the old structure, we will soon find ourselves entangled in a mess of well-known problems from the past. The good news is: We don’t have to choose between two extremes. There are ways to incorporate our learnings from the past three decades and combine the best of two worlds. We can design team structures that provide sufficient stability and good business flexibility at the same time. There’s obviously no one-size-fits-all, and each organization needs to find their own sweet spot.

If you want to learn more about this topic and hear both success and failure stories from companies that moved away from stable, cross-functional teams, you can attend our Team of Team training in Hamburg (in German). Or you can reach out to me for inhouse training / workshops in English or German.