Designing Multi Team Systems

30 Years ago, before the advent of Agile approaches, software was mostly built using the following approach: In our R&D organization, we had folks with different specializations like developers (back then mostly known as programmers), testers,designers etc. These folks were neatly organized into functional departments (engineering, testing etc.), which were their home bases, each led by a functional manager. This approach had some advantages, but also some serious disadvantages, which became more and more of a problem: Every time we wanted to build a piece of software, we had to assemble a project team, consisting of e.g. a designer, several developers and a tester. These project teams were given a list of requirements and a project plan, they divided up their work and then every individual worked on their respective parts and handed it over once it was done. Although very easy to understand and efficient in theory, this approach caused the same set of issues over and over again.

Issue 1: Misunderstandings about the requirements would only be uncovered very late in the process.

Issue 2: The individual pieces did not always fit together and this, once again, was only discovered very late in the process when it was tedious and time-consuming to fix.

Illustration 1: Building software using a project organization (simplified visualization of couse)

Issue 3: It was difficult to react to changes during the project.

The main reason for this was that the specialists were not only working on one project until it was done. Instead, they were assigned to different projects. This is mostly what made this approach so appealing: It was very efficient, because it allowed us to fully utilize our “resources”. One of the flip sides of this approach is of course that it takes a long time to react to change. If the developers discover that some re-design for project 1 is needed, the designer is busy with project 2 (and project 3 after this), so it might take a long time before they get to it.

Illustration 2: Every specialist is fully utilized, working on multiple projects

Enter Agile methods. Approaches like XP and Scrum offered great ideas for how to develop software in a better way. Instead of project teams, organizations started to build stable, cross-functional teams that could own functionality end-to-end. Instead of building software in one large piece, we started slicing it into small, value-added chunks (e.g. User Stories). Instead of working in isolation, we focused on ongoing communication and shorter feedback loops (e.g. through daily standup meetings). And instead of integrating everything at the very end, we learned technical skills (e.g. continuous integration and automated testing) that enabled us to integrate and deploy software continuously.

Illustration 3: Cross-functional team, whcih continuously collaborates and integrates their work

Multi Team Systems

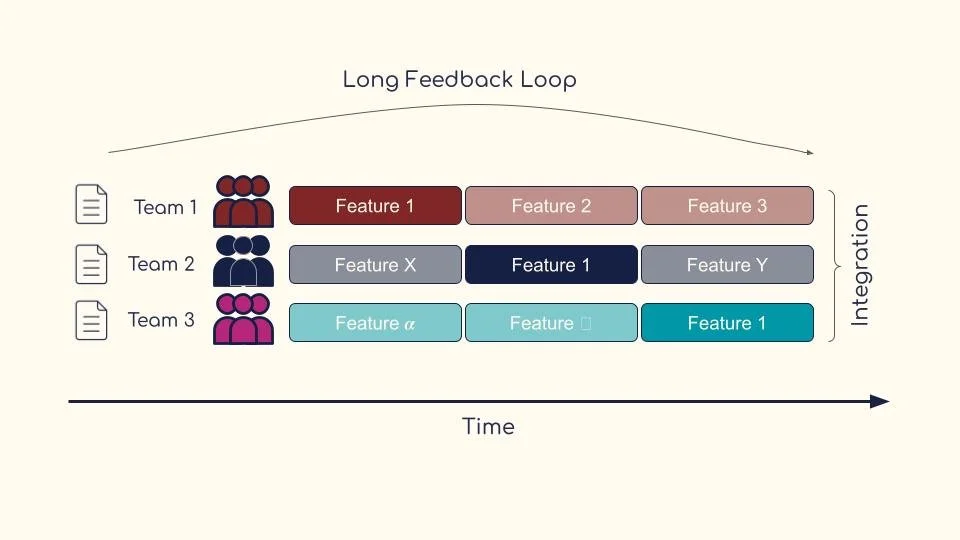

We obviously have learned a lot about software development during the past 30 years, and the old problems seem to be gone. So why am I telling you all this? Because we are now seeing the exact same patterns and issues again, only one level up. In today’s world, many organizations are not able to build new functionality with small, cross-functional teams alone. Instead, several of these teams need to coordinate their action in a multi team system. And although the individual teams might work in an Agile fashion internally, the teams often interact in an old-school style. When we start working on a big new feature, we often gather all the teams we think need to be involved, decide which team is doing what, and then each of the teams work on their respective deliverable. These deliverables will then be integrated once all the work is done.¹ If we visualize this process, we can see that it looks exactly like the one from 30 years ago - only that we now have teams instead of individuals as the basic units.

Illustration 4: In a multi team system the teams often work in isolation and hand over their work to each other.

And once again, the different teams do not only work on the one big feature. They work on several things, so that they are always fully utilized. It’s not surprising that we are now seeing the same problems in our multi team system, that seemed to be solved a long time ago: Misunderstandings might only be uncovered very late in the process. The parts often don’t fit together well (which we will only learn at a stage when it’s hard and expensive to fix). And it’s hard to react to change, because the teams are so busy, that it takes ages before they can shift their attention.

Illustration 5: Fully utilized teams in a multi team system

Team-of-Teams?

What’s the alternative? Analogous to building cross-functional teams that focus on one goal at a time, we can form a real team-of-teams: a highly cohesive unit consisting of multiple teams, which continuously coordinates their actions, in order to focus on a superordinate goal. Marcin and I have shared some of our ideas about how this can be achieved in this mini series of blog posts (part 1, part 2, part 3). It can be done, and we have seen it work. But it’s also true that it’s hard to build such a team-of-teams. The organization needs to invest in technical and social skills, it needs to unlearn certain behaviors and learn new ones (e.g. focus on flow instead of utilization), and there’s a price we have to pay (e.g. working on less things at the same time). Is it always worth it? Probably not. It strongly depends on things like the complexity and time pressure of our work and how big the pain is that we experience by our current ways of working. In any case, it should be a conscious decision how we design our multi team system. It could be a loosely coupled group of teams that work in a project fashion or a highly cohesive team-ot-teams (or anything in between). We just need to be aware of the trade-offs we are making and should not expect getting results that we did not design for.

__________

¹ I call this pattern “Divide-Conquer-Integrate” and have blogged about it in this post.